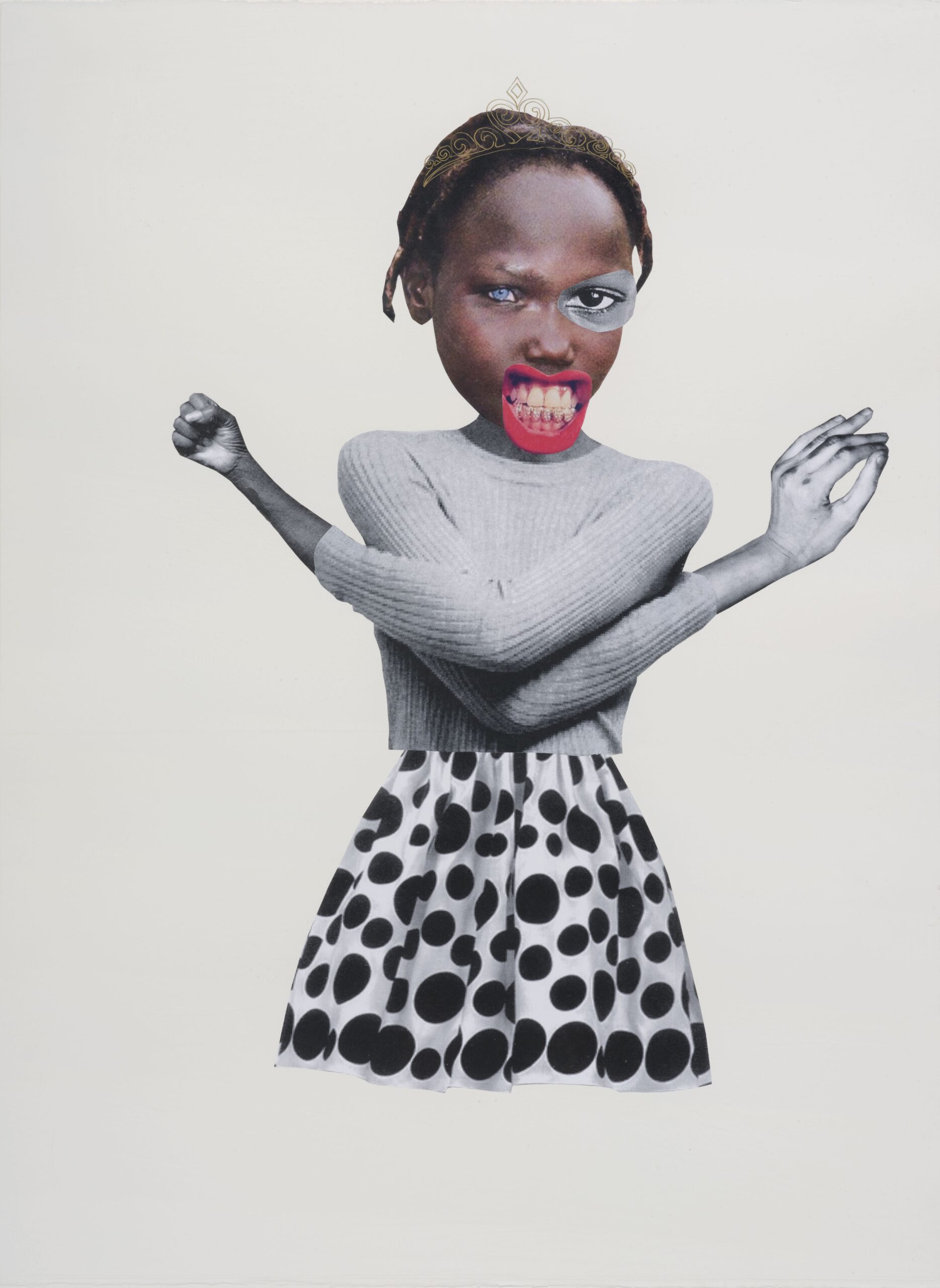

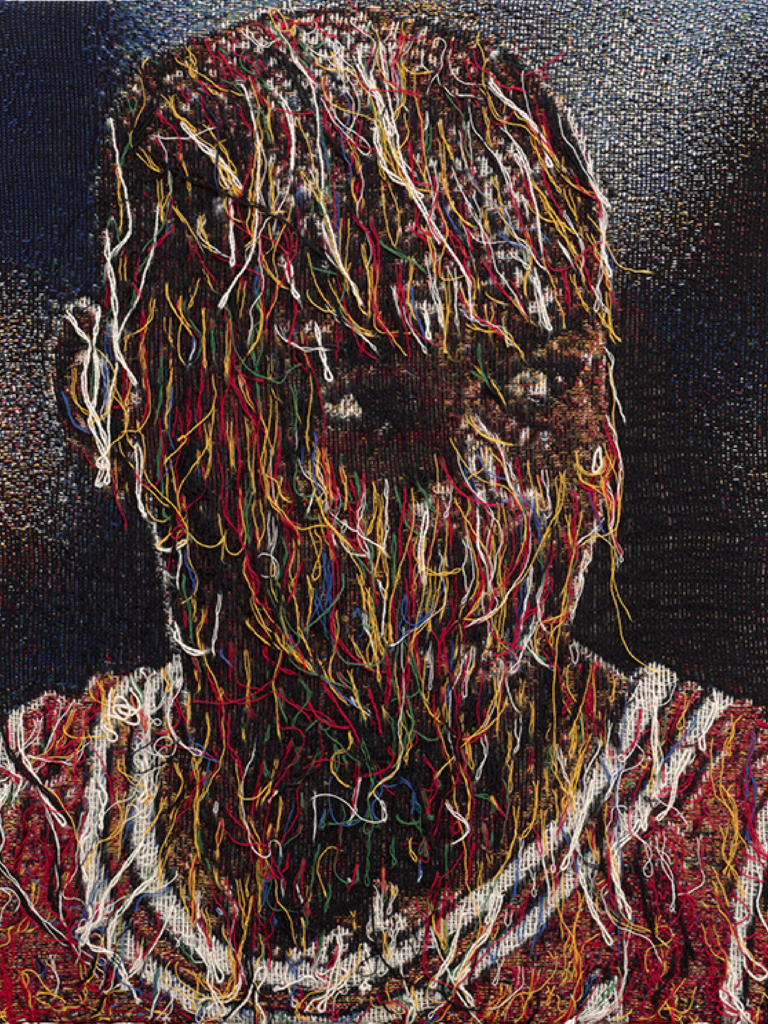

Deborah ROBERTS Radical, 2017. Mixed media and collage on paper, 88 x 67.5cm

We Can’t Stop Smiling: At the Opera Gallery

Alayo Akinkugbe's first solo-curated exhibition presents works by eighteen Black artists in London group show, 'The Whole World Smiles With You'.

Writing by Gazelle Mba

Photography by Eva Herzog

JUNE 2024 | REVIEW

Call and response. That’s what the Louis Armstrong song is about. The unsettling power of a look, a gesture to invite correspondence. I smile, you smile, we all smile. His lyrics, on the surface, appear deceptively simple: “Oh, when you smilin’, when you smilin’/ The whole world smiles with you/ Yes, when you laughin’, when you laughin’/ Yes, the sun come shinin’ through.” But when read against the specific conditions of his life as a black male artist in 1920s America, his words reveal hidden depths. A black man’s smile is never neutral; it is a magnet for meaning and interpretation. A black man’s smile turns the world on its head, provokes discussion, starts a movement.

Armstrong’s song captures the extravagance of black gesture. The uncanny manner in which a laugh or smile can exceed the bounds of an individual and move towards the collective. It is this touch of exaggeration, this ‘extraness’ that I find throughout the exhibition The Whole World Smiles with You at Opera Gallery. Taking its title from Armstrong’s “When You’re Smiling,” the show is a study and appraisal of black figurative art as it exists today.

Featuring artists from across the black diaspora—Jazz Grant, Aboudia, Simphiwe Ndzube, John Madu, Thelonious Stokes, and Chris Ofili are just a few names—the show stages a conversation about the status of black figurative painting in the contemporary art world. The paintings on display are not chosen for their ability to ‘represent’ an ‘authentic’ black experience; rather, they are selected for their more disruptive qualities. The works contradict and subvert the unthinking popularity of black figurative art.

(L-R) Adjei TAWIAH I’m still here, 2023. Oil on canvas with sponge, 80 x 80 cm | Amoako BOAFO Laced Fingers, 2022. Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm | Adjei TAWIAH Still Got Your Back, 2023. Oil on canvas with sponge, 219.7 x 210.1 cm

Over the past decade, interest in paintings by black artists that depict black people has risen steadily in the art market, in contrast to more abstract works by black artists. The most famous of the former group—Kerry James Marshall, Kehinde Wiley, and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye—are leading the way in international sales and exhibitions. But the problem with black figurative art, especially since the 2020 global uprisings against racism and police brutality, has been the way that the label has become a box that the art world stuffs black artists and black people in, like skeletons in a cupboard. Black figurative art is, at times, too neat, too tidy, a visual shorthand that allows white liberals to wash their hands clean of racist accusations while at the same time refusing to properly or deeply engage with the variety of black art and experience. When Louis Armstrong sang about the whole world smiling with you, he wasn’t just talking about mimesis, the replicas that unfurl from a single grin. His words speak to the ways that black people become trends and commodities. What we do, the world copies. But at the end of the day, the white man gets paid.

Curated by Alayo Akinkugbe, the founder of ablackhistoryofart and the podcast A Shared Gaze, The Whole World Smiles with You is an alternative vision of black figurative art. Akinkugbe’s curation is attuned to both time-honored works and the weird and offbeat. On display are the modernist-looking Untitled painting by Chris Ofili, a gouache on charcoal and gold leaf paper of two black lovers, trim as silhouettes, crimson lips locked in a kiss reminiscent of Rene Magritte’s The Lovers; as well as the zany and punning Still Got Your Back by Adjei Tawiah. Tawiah’s painting is a portrait of two bare-chested black men; one dressed in blue boxers carrying the other wearing white boxers with a sunflower print. A study in contrasts. The show excels at taking itself seriously but not too seriously at the same time.

Alayo’s distinct pairings offer a new way of curating black figurative art. She points out that despite the unpredictability of the art market and public opinion, “figuration will always be relevant.” But with the exhibition, she hoped to “nuance the idea of what black figuration is,” by bringing “together the works of emerging artists that [I] admire, with more established artists that Opera has access to.” The balancing of these different perspectives and relationships to the black figurative art canon is what makes the show visually striking—a walk off the beaten path of black art history. Taken as a whole, these paintings might not necessarily be speaking the same language or addressing one another directly, but there is a music to the subtle notes of discordance. The kind of pleasure derived from the refusal to match.

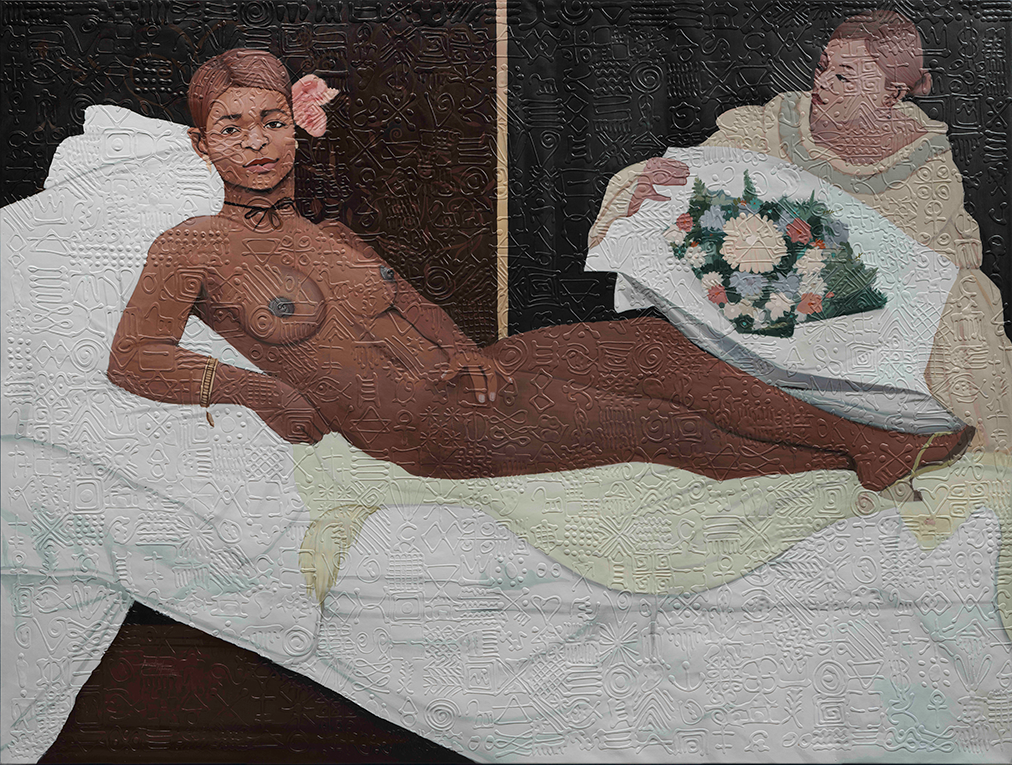

Awodiya TOLUWANI Ewa/Beauty, 2022. Acrylic on texturized canvas, 138 x 180cm

Awodiya Toluwani’s Ewa/Beauty is a pastiche of Édouard Manet’s famous Olympia painting of 1863, which features a prostitute in seductive repose while she is served by a black woman in the background of the painting. Manet’s painting was inspired by Titian’s Venus of Urbino, both classics of Western art history. Toluwani’s Ewa/Beauty reverses the race of the two women so it is the black woman who is served by the white. This role reversal paints a portrait of black female sexuality as freed from its typical submissive posture, finally able to take center stage, bold, triumphant. Ewa/Beauty is indebted to an older, classical tradition and is in keeping with the tendency of many black figurative painters to reconfigure poses and paintings from the Western canon for their own ends. But take a work like Jazz Grant’s She Leans Over the Earth. The black woman pictured leaning is faceless, a small afro her most prominent physical feature. Unidentifiable, she blends into her environment, becoming the earth on which she leans. It makes me think of how you can see someone and not see them at the same time. How often black people are misrecognized, mistaken by others, taken for the earth on which we lean.

Getting people to look, making noise, attracting attention. This is what black figurative art does well. Alayo notes that for curators and the upper echelons of the art world post-2020, black figurative art became the most relied on means of showing “the presence of a black artist… the easiest way to engage with people without much experience of black art.” These paintings were often eye-catching, visually arresting, positive, as Alayo says, in “stark contrast to the negative imagery” that surrounded George Floyd’s brutal murder. Much of The Whole World Smiles with You makes viewers look afresh. Instead of rolling out “positive” imagery to cynically counteract the depressing portrayal of black people in Western media, the show considers how shades of light and dark might exist in every representation of black life.

Noel ANDERSON Michael in Sound Suit, 2019. Distressed, stressed jacquard tapestry mounted on panel, 51.3 x 40.8 cm

Thelonious STOKES Tired of Being a N*gger; Champion of A Fowl; Crossroads red ribbons and chalk lines, 200 x 150cm

The Whole World Smiles with You is a blow to what Alayo describes as the “singular idea” of black figurative art. Multiple truths, realities, and perspectives are embraced. Blackness is not a monolith, and so black figuration cannot be either. One consideration of importance for her was “to highlight works by artists from different regions in the world so there would be a recognition of how blackness functions in different contexts.” The diversity of black art lies at the exhibition’s heart, alluded to not solely in the works assembled but also in the title. The “whole world” encompasses more than a single story. I came away from the show feeling that it wasn’t an exhibition centered on how or why black people paint black people; the black figurative paintings on display are more concerned with how black people show up in the world as multiple, variable, changing. Blackness here is a form of expression that moves beyond the individual and towards the collective. Oh, when you smilin’, The Whole World Smiles with You.

GIDA © 2024