Fossils of a Future Time

Anne-Lise Agossa Creates Objects That Exist Between The Past and the Future

Writing by Gazelle Mba

Photography by Anne-Lise Agossa

OCTOBER 2024

The Sahel encircles Africa’s wide torso like a belt. Or a piece of delicate corsetry worn to unify and not restrict. Stretching from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east; the Sahel is a space of transition, a place of becoming rather than being, where a range of climates and ecologies meet. Its topography is flat, though isolated plateaus and mountain ranges like the Marrah and Aïr Mountains rise up intermittently they do not disturb this unbroken rush of land, this steadily levelled earth.

Of its political life, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, The Gambia, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal and Sudan are the countries found within this geographic region. Each unique and possessed of clever idiosyncrasies, heaping distinction upon distinction, difference upon difference, and yet brought together by this ocean of dust and sand. Sahel is Arabic for ‘shore’ and this makes sense to me, the way it acts as an internal shoreline for those nations, constructing borders of its own agency and with the irascibility of desert sands undoing the borders we choose for ourselves. Making and unmaking, the Sahel does as it pleases. It serves no master.

It is no wonder why this stubborn land calls out to the imagination. Adonis said of the desert that ‘only poetry knows how to pair itself to this space.’ Words are compelled to the brown earth like forbidden lovers are to each other. It may be possible to leave the desert but the desert refuses your absence; it lives somewhere inside of you. The great Tuareg poet Mahmoudan Hawad wrote in Exile:

‘Where are the tents of long ago

impregnated with the indigo of the ahal ceremonies?

Where are the tents of times gone by

their entrances aligned with the horizon of the stars

the desert of border-free roaming?

Where have the seasons of swapping pastures gone

Courts of love and beauty?’

The desert is cloying, haunting dreams and verse, even after the poet’s departure. His questions release the particular distress of exile, its pain expunged by the invocation of spaces he once knew but are no longer there, no longer within reach.

In Hawad’s poem, the desert is marked by the impossibility of return, but most of all by its ceremonies and rituals: the displays of courtly love and beauty, the swapping of pastures among the tents of times gone by.

But the Sahel is not merely the subject of poetry; artists and designers also turn to the deserts and its myths. For designer and artist Anne-Lise Agossa, much of her work has been concerned with learning more about the civilisations and cultures that call the Sahel home. In September of this year, Agossa released a body of work titled Fossil. The collection drew inspiration from the macro and micro landscape textures found in the Sahel and West Africa. These textures are manipulated into objects that construct an alternative mythology of the Sahel.

When I interview Agossa in her studio in East London, she tells me about her interest in mythology: ‘We know about all sorts related to the Atlantic, but it's not very embedded in our regional culture to speak of or know or understand myths of the desert.’ The relative opacity of desert mythologies prompted her search for desert tribes. She closely studied the tribal composition of the Western Sahel and found that the Tuareg were the largest ethnic group in that region. She wanted to know more about them and use that knowledge to make objects that might strike sparks of fascination within us too.

This research culminated in an audio-visual storytelling project called Essuf. Here she explored a speculative, borderless future in the Sahel- an environment already resisting this very notion- where, as she says, 'traditions and myths from desert tribes are embedded, mixed and included in the national identities and cultural practices of myriad other groups.’ After the short film was completed, she began a new body of work that was, in part, motivated by the desire to uncover a different orientation to African history and its material production. This body of work became Fossil.

Anne-Lise Agossa was born in Togo and currently lives in London where she has a studio. She was raised between several West African countries, in particular Côte d’Ivoire. She credits her West African upbringing, alongside architectural education in the West and travels with informing her work. Her design work is inflected on by the ‘in-betweenness of cultures, identities and their visual markers.’ When we meet, she shows me one of her favourite books, Homi K. Bhaba’s The Location of Culture, which she describes enthusiastically as expanding her ideas of ‘Third culture’ and ‘what it is like to sit in between identities.’ These themes- third culture, being in between, displacement and dislocation- are the desert’s music, notes that resonate even with those who have never visited its dusty shoreline.

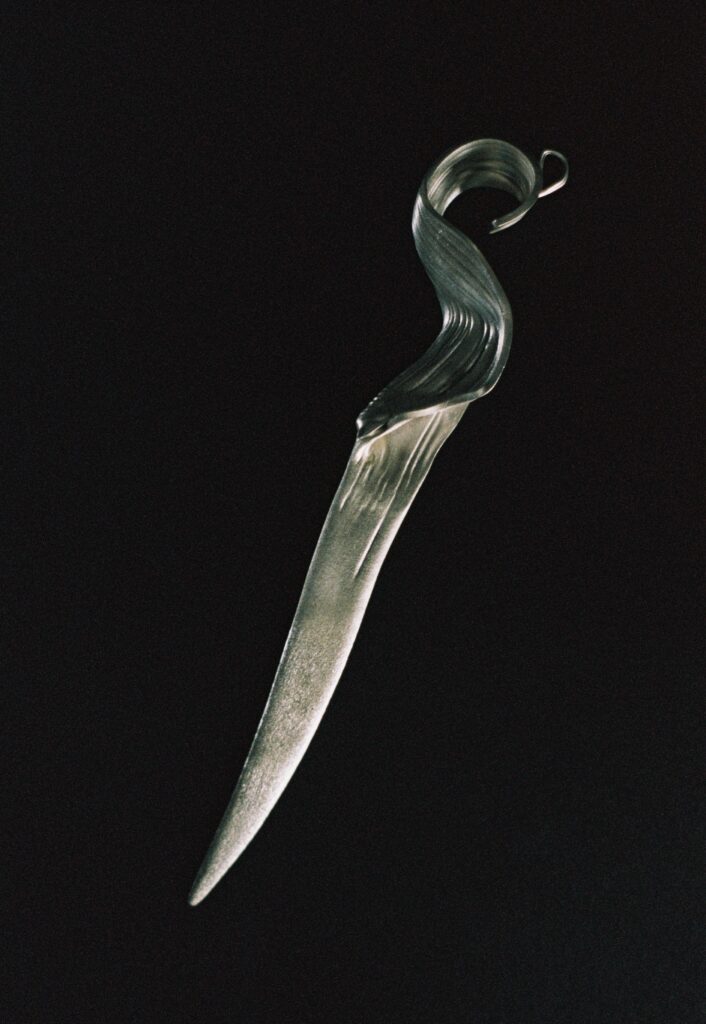

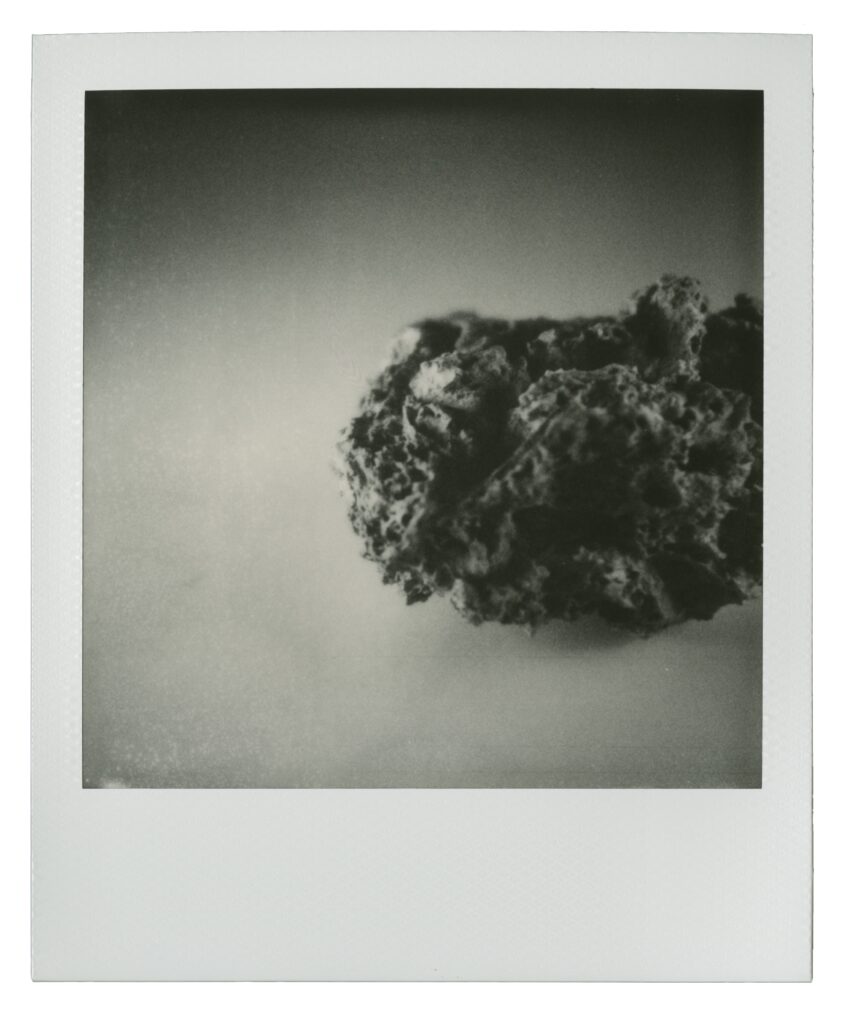

Fossil is composed of 6 objects: a perfume flask, a lighter case, a coral stone incense burner, a hibiscus holder, a wenge wood candle holder and a sterling silver letter opener. These objects are both items intended for day to day use as well as a system of ideas that reflect on the relationship between culture and space. Agossa’s work asks: does culture create space or is space created by culture? Put another way, how does a Tuareg poet create or recreate the desert landscapes of his birth or how did desert create him, shaping him into the poet he became? In attempting to answer this impossible question, Agossa's objects are deeply rooted in the West African and Sahelian context that inspired them. The origins of the object and its making cannot be separated. Object is context, context is object.

Agossa’s design practice begins with copious amounts of research. She talks to me about her extensive research archive, books ‘on different topics, ranging from architecture, materials, objects to belief systems, mythologies and fashion.’ Yet, the most consistent thread in her work has been West Africa and the Sahel, with a special interest in the once prosperous trans-Saharan trade routes which connected North Africa to Sub-Saharan Africa, and subsequently the rest of the world. These trade routes were used extensively from the 8th century to the 17th century. Through its focus on the materials that defined the route, metals, wood, flowers and plants, Fossil is a means of investigating the Sahelian past by teasing out the presence and consequences of the desert's expansion on contemporary African life.

The materials of her craft are most important. She is enamoured of metal, textile and wood, all three are hallowed in African material history. She identifies metal as being one of the earliest forms of currency in Africa, marking its symbolic and material value for centuries. The metal she is most drawn to is silver. Her first attempts at collecting silver jewellery at age 18 denote the origins of this fascination. On most days, the designer is not without a pair of silver earrings or a necklace. She does not wear anything else. Textiles too are a privileged part of her practice. Calico cotton was one of the currencies of exchange used to purchase luxury goods on the trans-Saharan trade routes. Textile manipulation, prints, embroidery and beading are the methods through which she incorporates the material in her design work.

Agossa’s recent collaboration with Ghanaian Studio Limbo Accra and Ivorian textile brand Super Yaya as part of the Sharjah Architecture Triennale 2023 is an example of this. Super Limbo, a public architecture intervention and installation was housed in the unfinished Sharjah Mall. Agossa was responsible for the project’s conceptualisation and design development. It featured interlaced yards of calico cotton designed by Super Yaya, hung and draped over the vacant brutalist structure. Super Limbo has been shortlisted for the Dezeen Award in the installation design category. As for wood, she offers: ‘wood carving and sculpting offers a connection to ancient African craft-making traditions that have helped conserve belief systems on the brink of extinction.’ She is currently working on a bigger furniture piece made from wenge wood.

To make these objects, Agossa works with artisans between the UK and Ivory Coast, often taking multiple attempts to achieve the desired texture and look. But to look at the objects themselves- the gleaming letter opener which appears almost like a thunderbolt snatched from the sky- you would not think of the effort involved in making them. They appear effortless, natural, like they have been plucked from the desert and burnished for our pleasure.

Fossil is marked by intimacy. These are objects, like the perfume flask and lighter, that you take with you; they live in your bag or your bedroom. It’s their sensuous qualities that are the most eloquent: the lighter’s cool, uneven surface resting in the palm of your hand, the scent of hibiscus and African musk candles greeting you after a long day. The intimacy of Agossa’s work makes them less of an intellectual exercise, they contain something of lived experience, traces of her desires and obsessions. The perfume flask and incense burner bring back memories of her mother burning incense in her house in Abidjan, where she always kept pot-pourri in every room. She says, ‘I’m sure many West Africans can relate to that experience too… Burning incense is a daily practice for me too today, the best compliment is when I have people over and they comment on how good my space smells.’

Agossa never wants her objects to be merely decorative or a means of satisfying one’s passive desire to look. These objects are intended to be a part of daily life, imbuing daily actions with meaning and a sense of history. When I ask who she designs for she answers simply: ‘I mainly make objects for myself and then I hope that other people love them too and want to own them as well.’ You can sense the love behind these objects; they invite a kind of tenderness that comes from the designer’s guiding belief that life can and should be beautiful. In her words: ‘I don’t travel without my perfume bottle.. I use my pot-pourri to fill my room with a pleasant smell, my candleholder to burn candles on a cosy night and my letter opener to open my mail. I strongly believe in beautifying your daily rituals, and these objects contribute to that. It helps me build up my world and live in it.’ Fossil isn’t a selection of curated objects, but a unified whole- a cosmos in miniature- where everything is related to everything else, except made more beautiful.

Though these objects are used daily, Agossa is aware of the passage of time. She does not design with permanence in mind. The coral stone incense burner, for instance, is a found object. As the ash deposited by each incense stick accumulates on the stone, the geology of the object changes over time. The object, in a sense, changes with you. I like that idea a lot: the objects we exist alongside are imprinted on by time and experience, just as we are. We live both with and through them. I think this is why Agossa looks back at the past so much, the backward gaze brings these stubborn markings into view. She ventures, ‘I try to create objects that exist between past and future, a sort of archeology for the future.’ This life lived backwards moves towards the future still, always returning to the places it began- a fossil buried in the desert sand.

Fossil is a prelude to a much grander work, who's next chapter - Between the Desert and the Sea- owes much to an 18-month curatorial and development project between designer Anne-Lise Agossa and curator-producer Moyin Saka. They first met in 2020 through a mutual friend, but by late 2023, Agossa was at a stage in her career where she wanted to explore and define her creative direction. Noticing the lack of support for emerging practitioners within the post-COVID landscape, Moyin offered her expertise. She provided guidance and consultancy, helping Agossa refine her ideas, secure funding, and prepare for her first solo show. The context of their design partnership is part of what gives Fossil its unique character. More than just a collection, Fossil is a noun reaching outwards. A gesture of relation and intimacy—a gift from Agossa to the world.

GIDA © 2024